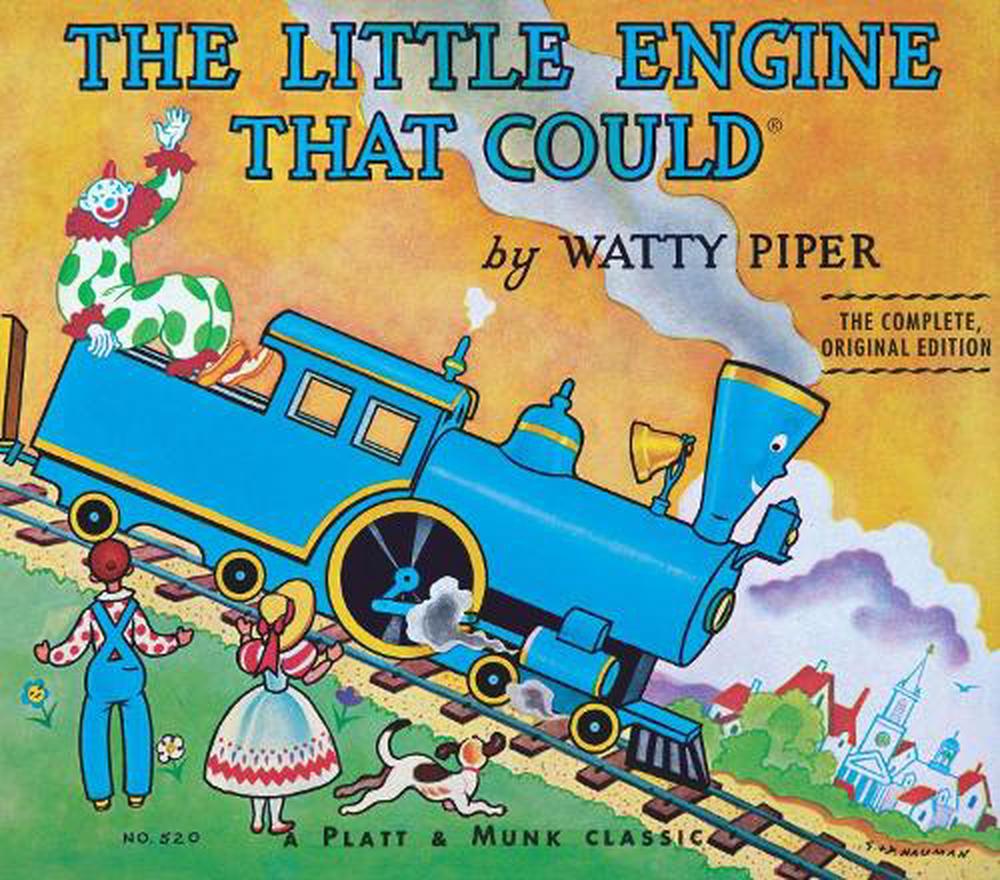

When I was little one of my favourite storybooks was one called ‘The Little Engine That Could’. I had the audio tape (yes, cassette tape) and I listened to it almost daily. It was about a little blue train that needed to get up a hill and prove that he could do it even though he wasn’t as powerful and big as the other engines around him. Now, being who I am and extremely stubborn and when someone tells me I can’t (even when I’m telling myself that I can’t), I like to prove to them (and myself) that, in the words of the little blue engine, ‘I think I can, I think I can’, I’ve changed that to, ‘I know I can.’

It took me forever to learn how to write a good essay. I was always told that I needed to include more evidence, elaborate on my ideas, vary my vocabulary, etc. It took a lot of practice and a lot of constructive feedback from my teachers as well as looking at sample essays and identifying the different elements of the structure for me to finally have that lightbulb moment and it clicked. It clicked at the end of Year 12. I guess that’s when it matters, but I did persevere, didn’t give up, and kept telling myself, just like the little engine that could that ‘I know I can’ and I did.

The text response essay is one of those essays that really requires you to apply all of your knowledge about the text and write about the meaning of the text that you’re studying. Most students are able to successfully provide summaries of the characters, and the themes, but in order to give your essays a little more zest, you need to add analysis by explaining how the writer has created meaning, but also what is the message that they’re conveying to the audience about the themes and ideas of the text.

One of the most important things that you need to remember is that you must engage with the key ideas of the topic. This has been the most common feedback that examiners identify in the examiner’s report. Students sometimes tend to memorise essays and then try to squish those ideas into the essay that they’re writing for the SAC/exam and think that they’ve nailed it. But unfortunately, these students haven’t made connections to the prompt and explored the implications of the ideas within the topic. Because of this, they lose marks even if their essay is written well. It could be the difference between an A and B or a study score of 40 or a 39. I have always told my students that memorising is to their detriment because of this reason. Examiners want to know what you know, not what you’ve remembered, and this engagement with the text gets rewarded. But how do you prepare for that?

Planning

For me, it is all about planning. I’m a huge advocate for the essay plan. The more you plan, the better your understanding of the topic. It’s about unpacking the question and asking yourself questions that are related to the prompt. This helps you consider its implications and get you thinking about how to structure these ideas into your paragraphs. You can write endless amounts of essays, but if you haven’t planned those essays correctly, then your whole essay ends up being a waste of your time and your teacher’s. But a plan that is planned and checked, is more efficient and means that you can then write effective practice essays.

When planning you need to think about the following:

- What is the big idea/theme of the question?

- What does this mean?

- What are they key words of the question?

- What is the question asking me to do? Discuss? Agree? Disagree?

- What questions do I have about the topic?

- What themes are connected to this?

- What evidence could be used to support these ideas?

- How does the writer illustrate these ideas through structural elements of the text?

- What message is the writer conveying?

This may seem like a lot of questions, but the more your practice and familiarise yourself with the planning, this will be a very quick process with little time for overthinking.

Once you have understood what the topic is asking you to discuss, start planning the structure of your essay and body paragraphs.

Be selective of the evidence that you choose. When you first start the planning process you might find that you’re copying and pasting your evidence into different paragraphs because it doesn’t quite fit where you thought it might. Take your time with your first plans and use all of the resources that you have. This may mean that your first plan takes over an hour, but once you have practiced this a number of times, you will have a better understanding of the text and feel more confident and the need to use the resources will not be necessary. And, the plans themselves serve as your study notes. Plan for a variety of different prompts, and study these plans before your SAC and exam, and then when a question that may be similar appears on the SAC/exam you already have an idea of how to approach it.

What to include in my analysis

When analysing a text you need to consider how the text has been constructed and what is the purpose of the characters and themes in creating meaning and conveying the message of the writer. Depending on the type of text that you are writing depends on the elements of the text and how it has been constructed, but for all text the following should be considered when planning your essay

- Setting – both the contextual setting and physical setting. When was the text written and what is the writer saying about society and their values at the time? When is the text set and where? How does that help to convey the message of the author?

- Characters – Most of you will be able to talk about the main characters and provide specific evidence about how they are able to represent a particular aspect of the text, but the minor characters also play a significant part and are there intentionally to convey an idea. Consider these characters when planning your essays as they are just as essential as the main characters.

- Themes – This is a given. What is the main theme of the topic, and what ideas stem from this? This will help form your supporting arguments and allow you to have a focus for each body paragraph

- Symbols – This is a given for every text. There will be symbols that create meaning and this will add to the analysis in explaining the implications of the topic and the message the writer is conveying

- Structural elements of the text – This is what will give your essay the zest it needs, when used correctly. This is the HOW part of your analysis. How does the writer convey meaning. Yes they do through the other points that I’ve outlined, but this is going into the intricacies of the text. For each text there are different elements to consider. Langauge and imagery is common for all of them, but consider the following for different forms (this list is not extensive, I’m sure your teachers would have gone into more detail)

Novels

- Chapters

- Perspective

- Dialogue

- Descriptions

Plays

- Structure (acts/episodes/scenes)

- Dramatic Irony

- Dialogue

- Stage directions

Poems (anthologies)

- Form

- Rythym

- Figurative Language

- Structure

Film

- Perspective

- Film Techniques

- Sound/music

- Lighting

- Costume

- Mise-en-scene

Short stories

- Style of the anthology and how the stories connect

- Perspective

- Use of specific language

- Tense

Memoirs

- Structure of time (chronological/circular)

- Perspective

- Shifts in tense

- Recurring motifs

Just remember, you can’t talk about everything. It’s impossible. You may have so much to talk about it and you may know your text inside out and want to show this to your teacher/examiner, but it’s all about what you have written and ensuring that you have selected the most appropriate evidence to demonstrate your understanding of the text and how that example explores the ideas associated with the prompt. You are marked on what you have written, not on what you haven’t. That’s why planning is so important, so that you are certain that the evidence you have chosen is the best evidence for the point that you’re exploring.

Just tell me how to write an essay

I have gone on a little bit about the planning and what evidence to consider when preparing for your essay, but now you have to write one and that’s what you’re getting the marks for. I’m going to provide you with what I teach my students, but if your teacher is providing you with other suggestions, then listen to your teacher. I’m not saying they are wrong and I am right, we all have different approaches and they work according to our cohort and our teaching. This is just how I do it, because I have students that like to follow a certain structure and this has worked for them. My stronger students will adapt to their style and other students who just need to follow a type of formula, it allows them to build strong arguments as well.

NB: The sample work that has been included references the play ‘The Women of Troy’ by Euripides, but the same rules will apply to any text.

There are a couple of rules that I go by and reinforce to my students.

- Make your arguments thematic. Avoid being specific about characters in your topic sentences and instead use them in your examples. Topic sentences should develop an argument about an idea that directly links to the contention and the key ideas of the prompt. If a character is central to the prompt, you would make that character a focus of your essay, but you would still ensure that each paragraph is also focusing on a key idea associated with the prompt.

- Use two examples per paragraph and ensure that you make a connection to how the writer has created meaning through the structural elements of the text. Just choose one per paragraph.

- Avoid saying ‘this shows’ and instead make that an author statement, (i.e. Euripides illustrates…) to make your writing sound zesty and it suggests that you understand that the text is a construction and a vehicle for the author to present an idea and convey a message to their audience.

- Include quotes in every paragraph. You will not be penalised for getting a couple of words wrong in the quote, but if you make up a quote, that will be obvious. Know your text.

- Also avoid using personal pronouns such as ‘we see this through….’ ‘we are positioned’. Instead focus again on the author or state the audience to make reference to the contextual setting.

- Avoid using the same example twice. You can use the same character more than once (especially if the topic is character focused then they should be included in every paragraph), but make sure the evidence is different and relates to the topic.

Introductions

Don’t make these long and regurgitated from study guides introductions. The examiners noted that many introductions started off in a similar way and that the phrasing was taken directly from sample essays and study guides. They did mention that high scoring essays engaged with the prompt immediately. That should be the focus of your opening sentence when you introduce the text. A good introduction doesn’t have to be long, but has to explore the implications of the key ideas of the prompt through the supporting arguments that connect to the contention.

Structuring your introduction

1.State the big picture of the text linking to the big idea in the prompt. Engage with the topic from the outset rather than writing a memorised sentence that has nothing to do with the prompt. Use the big ideas that are in the question to guide you, but also introduce the text.

2.Present a contention which outlines the argument that you will be exploring that directly engages with the prompt. Consider what the prompt is asking you to do by discussing or agreeing.

3.Develop supporting arguments which reveal that you have explored the implications of the prompt and ensure that they are linked to the thematic ideas of the text which will form the basis of your paragraphs that will be analysed in depth.

Body Paragraphs

I tell my students to write three body paragraphs, but make them good. Each paragraph should have a clear focus that connects to the topic and explores a theme/idea associated with the main idea of the topic. They should select two pieces of evidence from the text that explains how this point is explored by the writer and supports the message they are conveying. Choose symbols and structural elements to incorporate with each example. At the end of each example link back to the topic with an author statement. Close the paragraph with a linking sentence that makes a statement about the message that the writer is expressing about the idea in the paragraph as well as the prompt, avoid summarising what you have discussed in your paragraph.

A colleague who I worked with introduced me to the TCEEEEL structure and I have been preaching it ever since. I like to say that it is TEEL on steroids because it’s a buffed up paragraph with a bit more muscle which gives it the zest I’m looking for. What does TCEEEEL stand for?

Conclusion

The conclusion resolves your understanding and arguments that you developed and discussed concerning the prompt. Your conclusion shouldn’t be a summary of each of the points that you’ve talked about in each paragraph, but it should focus on affirming the contention that you have presented and the overall message of the text in relation to the topic. It shouldn’t be long, it should be concise but effectively provides a resolution to the topic.

One of my pet hates is when students write ‘In conclusion’ ‘Ultimately’ ‘Overall’ and my all time favorite ‘In a nutshell’ to start their conclusion. You don’t need to use signposting (and don’t use it for your paragraphs either). It is obvious that you’re concluding, (it’s also obvious that you’re writing another paragraph – you don’t need to tell me). This was fine in Year 7 when you were learning how to write an essay, but you are in Year 12 now, those training wheels should have been removed years ago. My students ask me what to write instead and I simply say to them to start the sentence with what you have said after the ‘In conclusion.’ When finalising your conclusion with that final point though, that’s when you can use concluding language.

Include the following in your conclusion:

- Reiterate the key idea in response to the essay topic in a core topic statement

- Further information about the statement (elaborate on the idea)

- Big picture statement linking to the author’s purpose and ideas that link to the question

In conclusion

The key advice that you will hopefully take from this post is the importance of planning. Planning for an essay is never a waste of time, but writing a complete essay that has not been planned effectively or interpreted incorrectly is a waste of time. Write plans for all types of questions. Develop a vocab list of words that are connected to the key themes of the text that you’re studying (remember the vocabulary that you use, could be expressed in a different way in the prompt). Put together a word bank of language that you use regularly such as your analytical verbs and transitions.

This post may be a little late for some of you who have already completed your SAC, but it is relevant for your exam, but also relevant for any year level (especially Year 10 and 11) for your text response essays. Unit 2 English will be completing these essays in semester 2, and it appears twice for the new study design in Units 3 and 4 for 2024 and the same rules apply. It is a skill that is evolving with your understanding of English.

As always, please get in touch if you have any specific questions, happy to help out.

Keep it zesty

Ronnie

For those of you who want to hear the story of ‘The Little Engine That Could’, here’s Dolly Parton reading it for you. Because why not?!